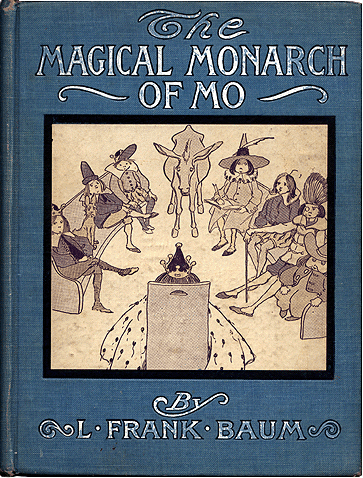

Although The Magical Monarch of Mo (under the title of A New Wonderland) was originally published in the same year as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, L. Frank Baum actually wrote the work a few years earlier. As such, it serves as a fascinating look at Baum’s original experiments with fantasy literature, presenting some ideas and characters that he would later rework in future books, while retaining the freshness of an author not yet locked into a popular series or writing style.

The Magical Monarch of Mo is less a novel and more a series of loosely connected stories (called “Surprises” by Baum) set in the land of Mo. Mo is an even more fantastic and fabulous land than Oz: it rains lemonade, has a river made of rich (and presumably very high fat) milk with cheese islands and floating bits of fruit; sands made from sugar, and candy growing on trees. Some cows actually give ice cream instead of milk. (I have absolutely no idea how this would work biologically given the generally warm insides of a cow.) Not surprisingly, in many illustrations, the people of Mo look comfortably plump. (Baum was never to lose his near obsession with easily obtained and abundant food.) Anything else that anyone else could possibly want grows on convenient trees, and no one ever dies or gets old.

Then again, people can still lose their heads and need a replacement. And dragons can show up and eat all of the very best candy. And even the most marvelous paradise is bound to run into occasional problems with quarrelsome animal crackers.

It might be thought that, head replacement issues aside, such a paradise would offer few possibilities for stories of any kind, much less fourteen of them, but Baum solves this in part by creating threats, both inside and outside Mo: people (and creatures) that want to destroy the land or the people (or creatures) within it, from pure envy. In a few tales, the people of Mo journey outside their land, attached to kites or giants, and return on root beer rivers or by other magical methods. And in other tales, the people of Mo run into their own problems—bad tempers, unrequited love and those lost heads and toes.

Each Surprise is its own little fairy tale. Some follow the traditional fairy tale format quite closely, featuring a prince or princess going on a quest, often with the help of a friendly magical animal or witch. As in many fairy tales, things usually happen in groups of threes: three tasks, three attempts to replace the king’s head, three caves with guardians to placate to reach the Wicked Wizard who has the princess’s toe. (The toe is a somewhat original touch.) Baum was later to mostly abandon this structure, but here, even in a tale bursting with fantastical nonsense, he retained several fairy tale tropes—even while including puns and incidents that would never have appeared in any edition of Grimm’s Tales.

For that matter, the stories are considerably softened from their Grimm equivalents (which in turn were considerably softened from their oral sources). Since no one can die, even losing body parts presents no more than a trifling (and temporary) inconvenience. And body parts can always be replaced—by candy (although that melts in the lemonade rain) or bread (although birds eat it) or wood (which makes you a little hard headed—and no, Baum was never to lose his taste for jokes of this sort either.) No one is ever in any real danger, even when squashed to paper thin sizes, robbing the tales of any real suspense, even as this creates a decided feeling of comfort and warmth.

In a nice touch, the princes, princesses, a dog and a forty-seventh cousin of the king all share equally in adventures. A few characters reappear here and there, helping to link together the various stories—particularly the Magical Monarch himself, head fully restored, and the chief villain, a Purple Dragon with a taste for plum puddings. (I always knew dragons had to have a sweet tooth.) Even with these links, the stories can be read individually and in any order, except for the last two.

Baum was to later claim that he wrote for the young and old, and although I think that’s true for the Oz books and some of his other fantasies, the text here feels unquestionably aimed at children, with relatively simple vocabulary, short sentences and paragraphs, and exceedingly silly jokes. (Amusing though the book is, I suspect it’s still more amusing if you are four.) And the book contains none of Baum’s later swift jabs at American society and human foibles. Even the adult characters often act in surprisingly childish ways, using childish logic to solve problems. (Mo being a fairyland, this works better than you might expect.) And the episodic nature of the book does make it, I admit, one of Baum’s slower reads, easy to set aside for a few days.

And yet, this book contains several magical moments and ideas: not just the cold root beer river (what a lovely, if sticky, place for a swim), but also a conversation between a dog and a king about the proper number of feet, a princess saved from a lake filled with sugar syrup with a kiss, flattened princes who must be pumped up with air. It also contains some ideas that Baum would later reuse in his later Oz books: immortal inhabitants, picking food and other useful items from convenient trees, and human creatures made of very inhuman substances indeed. And despite a rather brutal scene where various annoying Wise Men (who have not been very wise) are poured into a meat grinder and turned into a single Wise Man, the book is filled with something I can only call charm. It may be less funny than other Baum books, but it has far more warmth and comfort. It’s an excellent book to read to a child, or to escape back to childhood with, to a time when it was easy to believe that your head could be replaced by candy at a moment’s notice, causing you to be decidedly wary of lemonade rains.

Mari Ness is not certain that she would want to swim in a river of milk, although the root beer sounds tempting (if sticky.) She lives in central Florida.